From the Archives: The End of an Era

The following story written by John Steinbreder was published in the February/March 2000 issue of The Met Golfer. It's also available for viewing as a PDF.

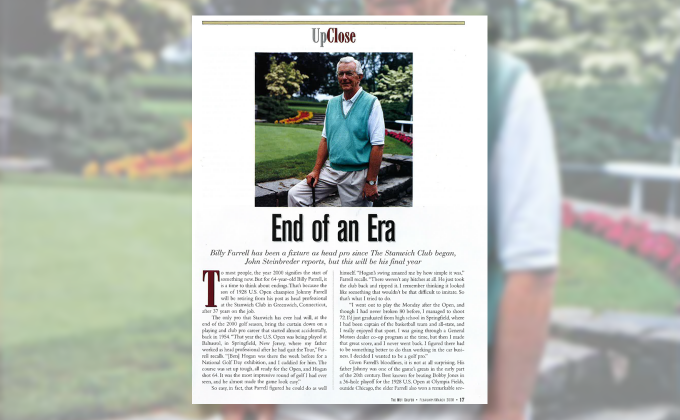

Billy Farrell has been a fixture as head pro since the Stanwich Club began, but this will be his final year.

To most people, the year 2000 signifies the start of something new. But for 64-year-old Billy Farrell, it is a time to think about endings. That’s because the son of 1928 U.S. Open champion Johnny Farrell will be retiring from his post as head professional at the Stanwich Club in Greenwich, Connecticut, after 37 years on the job.

The only pro that Stanwich has ever had will, at the end of the 2000 golf season, bring the curtain down on a playing and club pro career that started almost accidentally, back in 1954. “That year the U.S. Open was being played at Baltusrol in Springfield, New Jersey, where my father worked as head professional after he had quit the Tour,” Farrell recalls. “[Ben] Hogan was there the week before for a National Golf Day exhibition, and I caddied for him. The course was set up tough, all ready for the Open, and Hogan shot 64. It was the most impressive round of golf I had ever seen, and he almost made the game look easy.”

So easy, in fact, that Farrell figured he could do as well himself. “Hogan’s swing amazed me by how simple it was,” Farrell recalls. “There weren’t any hitches at all. He just took the club back and ripped it. I remember thinking it looked like something that wouldn’t be that difficult to imitate. So that’s what I tried to do.

“I went out to play the Monday after the Open, and though I had never broken 80 before, I managed to shoot 72. I’d just graduated from high school in Springfield, where I had been captain of the basketball team and all-state, and I really enjoyed that sport. I was going through a General Motors dealer co-op program at the time, but then I made that great score, and I never went back. I figured there had to be something better to do than working in the car business. I decided I wanted to be a golf pro.”

Given Farrell’s bloodlines, it is not at all surprising. His father Johnny was one of the game’s greats in the early part of the 20th century. Best known for beating Bobby Jones in a 36-hole playoff for the 1928 U.S. Open at Olympia Fields, outside Chicago, the elder Farrell also won a remarkable seven tournaments in a row in 1927 and played on the first two U.S. Ryder Cup teams. But shortly after the birth of his first child in 1933 (Billy was the third son after Johnny Jr. and Jimmy), he went to work at Baltusrol, where he stayed for nearly 40 years.

It took Billy Farrell four years to become a PGA professional, and it wasn’t long after that that he started making his mark as a player. He won the 1961 New Jersey Open and qualified for the U.S. Open that same year, finishing only eight strokes behind winner Gene Littler. He also made it into the 1961 PGA Championship and did so well (top 32) that he was given an exemption on the PGA Tour the following year. “I’d become my dad’s assistant at Baltusrol in 1960,” recalls Farrell. “And after I did so well in those big events, I had a club member, Karl Badenhousen, owner of Ballantine’s beer, sponsor me on the Tour part-time for the next couple of years. I wanted to see how I would do.”

A long hitter who frequently outdrove even Jack Nicklaus in competition, Farrell became known as the “Springfield Rifle”—a play on the name of his hometown and gun manufacturer from Illinois—and made some money in several of the Tour events he played the following two years. But it was not an easy life, especially with the long car rides between venues, and his young wife Alvera and infant son Billy Jr. in tow. And they all seemed to enjoy returning to Baltusrol in the spring and staying put until the next fall.

So it really wasn’t that difficult a decision to make in 1963 when the founders of the new Stanwich Club asked Billy to sign on as their head pro. He was 28 years old, his wife was pregnant with their third child and he was ready to settle down. So he said he would, provided he could play in major tournaments, both locally and nationally. With the terms agreed upon Billy Farrell, as his father had done before him, began a long-term relationship with a prominent Met Area club. “Sure, there will always be part of me that wishes I could have played the PGA Tour full-time,” he says. “But I know so many people that did it who are now divorced and never see their families. For me, things have worked out very well. I got to play in a lot of competitions and at the same time I got to be home most of the time with my wife and children. It really has been the best of both worlds.”

In fact, in his later years at Stanwich, he spent time with his family at home and at work. His son Bobby was his assistant pro, and his daughter Susan worked behind the counter in the spacious pro shop. At any rate, Farrell continued to fare well as a tournament player, qualifying for eight U.S. Opens, seven PGA Championships and four PGA Senior Championships. In addition, he has played in 15 Crosby Pro-Ams (now sponsored by AT&T), won the 1964 Met PGA Championship from a field that included Dave Marr and Doug Ford, was runner-up in the 1967 Met Open, and captured the Westchester PGA Championship and Westchester Senior Open.

“One reason Billy has done well in so many tournaments is that he has a great swing and has always been very good at course management,” says Tom Joyce, a former assistant of Farrell’s at Stanwich and a longtime friend and playing partner. “But the thing about him on a golf course that really stand out to me is his composure. He aways walked tall (He’s six-foot-three) and you could never tell from his body language whether he was shooting 63 or 83. He always had the same attitude, and I have never seen him give up.”

Farrell always carried himself well at Stanwich, earning praise as an excellent teacher who truly understands the golf swing and a man who knows how to run a tournament—as well as an entire golf program—without flaw. “Billy has meant so much to this club over the years,” says club president Eddie Laux, a longtime member who started caddying at Stanwich as a teenager. “In addition to running a great golf program, he has also been an invaluable help with his knowledge of the course and the way it should look and play. We are going to miss him a lot.”

Farrell is going to miss Stanwich, too, and you can see that in his eyes as he talks about his career at the club. “I’m not leaving completely, and hope to be around the club a bit after this season,” he says. “But it will be tough to give all this up.”

And it is easy to understand that as Farrell sits behind his office above the pro shop and looks around the walls covered with mementos from his—and his father’s—career in golf. There are shots of Billy and Sam Snead at Stanwich, a picture of his father and Bobby Jones at the 1928 Open, a photo of Johnny Sr. with Babe Ruth and Gene Sarazen, and portraits of his children and grandchildren.

“I’m not really looking forward to leaving,” says Farrell as he walks through his shop. “It will be a big change. I’ve been doing something good for 36 years, and pretty soon things will change. I’ll just have to wait and see how I do without it all.”

Billy Farrell will surely do just fine without it all. But that doesn’t mean his retirement from Stanwich won’t be felt by the members at Stanwich and the many friends he has made during what has been a remarkable career.